No Happy Medium for Books

A court ruling curtails the circulation of the written word

by Dan Cohen

Last year in The Atlantic, I wrote about an important lawsuit, Hachette Book Group, Inc. v. Internet Archive, that held the potential to reshape the way that books are sold, stored, and circulated:

It’s a story about the halting, uneasy transition of books from paper to digital formats, and the anxiety of publishers and frustration of librarians about that change.

In short, the Internet Archive was distributing scans of physical books it owned as locked-down, self-destructing PDFs, generally on a one-digital-loan-to-one-book basis, except for a brief period early during Covid when it broke that principle, expanding the loans-to-books ratio as libraries closed. Lawyers for the publishers sensed that this would be the ideal time to strike against this emerging practice of “controlled digital lending” (CDL), which many libraries beyond IA had been considering, or even starting to practice in small numbers, as a way to make new and better use of the collections they had paid for and preserved, and to serve their patrons.

The complaints of publishers and (some) authors were easy to understand, with a central emphasis on the marketplace: They alleged CDL would reduce their revenue and compensation by providing free competition. (One might note that this could be said of any circulation from a library; part of the difficulty of explaining this case with nuance is that, post-Napster, every form of non-commercial digital distribution is immediately likened to Napster, even if that distribution is modest and restricted.) Invisible to the broader reading public was the squeeze that is increasingly put on libraries by ebooks, which cost far more than print books, and are rented rather than owned, a sharp departure from last century’s healthier publisher-library relationship.

This is the issue I tried to highlight in my article last year:

If the decision [of the lower court] stands, libraries will lose the agency to digitize and lend the print books they have collected and stewarded, and instead will have to defer to, and pay, publishers for separate digital editions of in-copyright books. Over time, this ruling may change the very nature of libraries—how they operate, their finances, whom they are able to serve, and the breadth of their collections…

Most libraries do not even own ebooks in the true sense of ownership. The best they can do is to license ebooks for a limited time, or for a limited number of circulations, before they have to pay again. Even with these restrictions, ebook prices for libraries are much higher than for individuals — up to four times as much for a two-year, rather than a perpetual, license. Librarians are thus forced to make painful decisions: Should the library have a diverse collection, with a wide variety of authors and genres, or license many copies of the most popular books to reduce those long wait times? The worst part is that if libraries stop paying each year to renew ebook licenses, those ebooks will simply disappear, unlike the books on the shelves.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit has just spoken, giving little weight to the concerns of libraries compared to the concerns of publishers and authors. The court thus affirmed the decision against IA, and by extension, libraries.

In weighing the four factors of fair use, the court focused largely on the harm CDL might have on the market for books, and dismissed any “transformative use” that such digital loaning might have:

Is it “fair use” for a nonprofit organization to scan copyright-protected print books in their entirety, and distribute those digital copies online, in full, for free, subject to a one-to-one owned-to-loaned ratio between its print copies and the digital copies it makes available at any given time, all without authorization from the copyright-holding publishers or authors? Applying the relevant provisions of the Copyright Act as well as binding Supreme Court and Second Circuit precedent, we conclude the answer is no.

* * *

So what does this mean for the future of books, not just as objects to be created and valued as commercial products, but to be treasured as rich repositories of culture, which should be accessible not only to current paying customers but by curious audiences who are distant in space and time?

Libraries cannot in many cases even rent an electronic version of a book from its publisher. My research library leases over 1.6 million ebooks, a substantial collection with a substantial yearly cost, one that is well beyond the financial ability of most libraries and almost all public libraries. But even this generous collection fails to contain tens of millions of books that we cannot accession as ebooks, for the simple reason that these books do not have digital surrogates for sale.

A small minority — perhaps 20% — of the over 100 million books ever published are in the public domain, and you can freely read many of them in digital formats in Google Books, HathiTrust, or the Internet Archive. But a surprisingly large percentage of books — perhaps 80% — have been published in the last century and technically remain in copyright, and thus governed by this new court ruling. Few of them, however, will ever be made into ebooks. Most of them are “orphan works,” in which the copyright holder is unclear or cannot be located, or are out of print — long past their commercial lifetime.

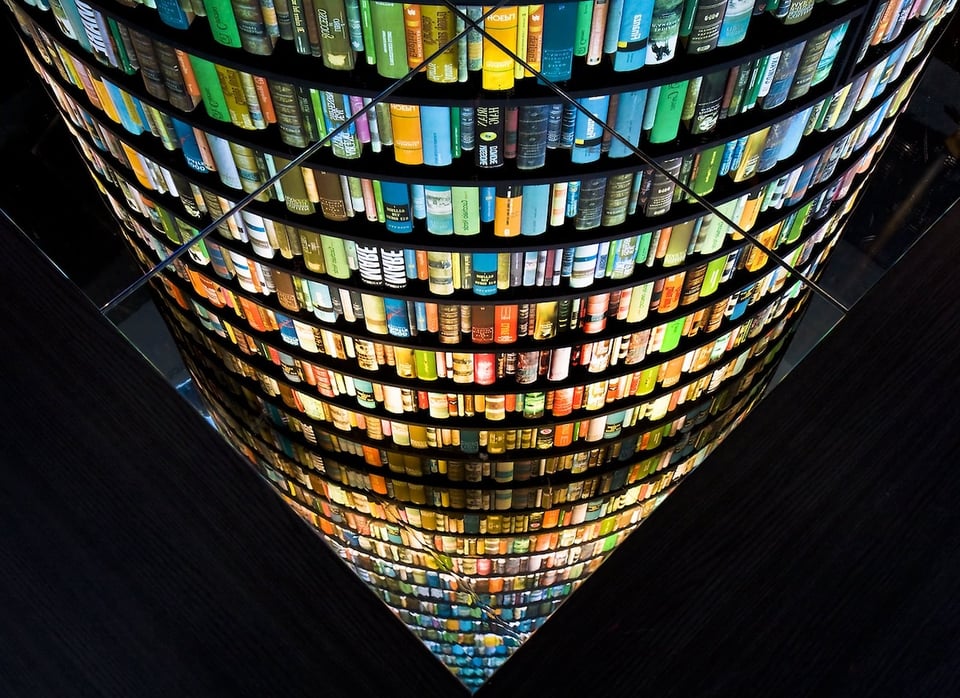

The universe of books is therefore like an iceberg that is mostly submerged and invisible, millions and millions of volumes that are largely inaccessible unless you have direct access to a massive physical library. Will libraries be able to bring light to the dark part of this gargantuan collection, providing digital access to readers who live at a distance or who prefer an ebook to paper?

A copyright regime that precludes libraries lending scans of books they already own and care for — to loan in-copyright works sometimes, for some reasons — ultimately will curtail the circulation of culture and prevent the preservation of it in the first place. Libraries can’t save and distribute what they can’t buy outright, or convert on their own into useful new formats. Right now there is no happy medium in digital media for books, no balance between the many stakeholders involved in the transmission of the written word.

* * *

A glimmer of hope comes from Digital Public Library of America and its new agreement with the Independent Publishers Group:

Through this landmark collaboration between IPG and DPLA, libraries around the country will now have the power to purchase and own in perpetuity, rather than merely license, tens of thousands of ebook and audiobook titles from dozens of independent publishers. The agreement will empower libraries to fulfill their mission to provide access to books for readers nationwide…

Since the advent and spread of digital content, libraries have only been able to license ebooks and audiobooks from publishers and aggregators with no option to buy, trapping libraries in licensing agreements where they must spend more money for fewer books that they do not own. Instead of being spaces where readers can explore emerging authors or more uncommon works, libraries have been under pressure to focus on bestsellers and titles by big name authors that are in high demand. A growing number of library leaders recognized that having to rent ebooks and audiobooks prevented them from fulfilling their mission of collecting, preserving, and ensuring long-term access to books for all readers.

Transformative agreements such as these will be essential to restore the long-term vibrancy of the ecosystem of books, along with sensible tweaks to copyright law that allow libraries, at the very least, to digitally lend books that are out of print or orphaned, and thus obviously not in competition with commercial ebooks.

(Full disclosure: I used to be the executive director of DPLA, and remain its cheerleader. But still, if you love books you should cheer this agreement.)