Humane Ingenuity 16: Imagining New Museums

by Dan Cohen

David Fletcher is a video game artist in London who on the side creates hyper-realistic 3D photogrammetry models of cultural heritage sites and works of art, architecture, and archeology. I particularly like how he captures soon-to-be-obsolete aspects of the city he lives in, and our modern life, like the beautiful cab shelters for hackney carriage drivers:

Last week, instead of focusing on a building or piece of material culture, David focused on a person, and the results caught me off guard. He captured one of the few remaining mudlarks in London, Alan Murphy. Mudlarks dig through the shores of the Thames to find historical artifacts, an old and now mostly bygone hobby. David took over 200 high-definition photos of Alan, and processed them in Reality Capture (for Alan's body and the surrounding landscape) and Metashape (for Alan's head).

The model is so realistic and detailed that you can rotate it and even zoom in on what Alan has found in the mud:

Not sure about you, but I find this simultaneously unsettling—in an uncanny valley sort of way—and also moving—like a Dorothea Lange photograph. And it's a strange flipside relative of the deep fake—a shallow real.

When they build a Museum of the Anthropocene, this very well may be one of the dioramas.

I have long admired the work and cleverness of George Oates, an interaction designer who cares deeply about libraries, archives, and museums, and has thought about how to further their mission through open web technologies. (She was behind Flickr Commons and Open Library, in addition to her stellar design work at Stamen and Good, Form & Spectacle.) So when George contacted me in a few years ago about her latest project, to create a small digital museum device, I was instantly in as a supporter.

That device is now out in the wild: Museum in a Box. Powered by a Raspberry Pi, each MIAB contains a special collection and stories or evocative audio about that collection, which you activate and hear by "booping" RFIDed items on top of it. Here's a brief video showing how the Box works:

The Smithsonian now has 30 MIABs, and globally you can see what people are booping over at the Museum in a Box Boop Log.

(Side note: really looking forward to OED's future definition and etymology of "boop," after the influence of 2010s internet culture, including We Rate Dogs.)

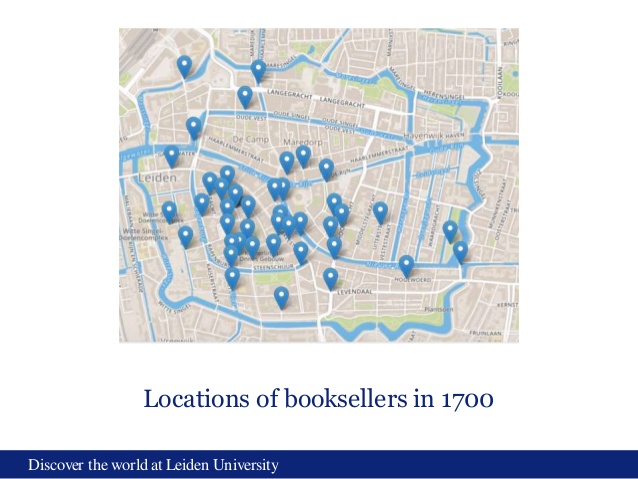

A little follow-up from HI15 on the recovery of independent bookstores: Book historian Paul Hoftijzer spent decades researching the early book industry in Leiden, and Leiden University's Centre for Digital Scholarship has now converted Hoftijzer's paper records into data. Peter Verhaar recently gave a presentation based on this data, and two things struck me. First, look at how densely packed the booksellers were in the relatively small city of Leiden in 1700:

Second, Leiden also experienced a painfully familiar boom and bust in bookselling that is clear in the data:

We should enjoy those independent bookstores while we have them.

In HI1 I mentioned "hard OCR" problems as good examples of the potentially beneficial combination of advanced technology and human knowledge and expertise. Tarin Clanuwat and her colleagues at Japan’s ROIS-DS Center for Open Data in the Humanities have recently made significant advances in converting documents written in Kuzushiji, the Japanese handwritten script used for a millennium starting in the 8th century, into machine-readable text. As Tarin notes, this could potentially open up entire new research areas in history and literature, because even among Japanese humanities professors, fewer than 10 percent can read Kuzushiji. Currently most Kuzushiji documents have not been encoded and are not full-text searchable.

The technical paper from Clanuwat et al. is worth reading as well for the holistic approach they took to analyzing each Kuzushiji page.

You may have read "An Algorithm That Grants Freedom, or Takes It Away," about the software that increasingly guides judges in their criminal sentencing and parole decisions, in the New York Times this weekend. Northeastern University researcher Tina Eliassi-Rad has been working on how to reframe and redesign those kinds of algorithmically determined (and often life-changing) automated processes. (I interviewed her about this on What's New, episode 18.)

Some of her main points:

- Only allow the machine to train on highly vetted, conscientiously assembled data sets that are independently verified for bias reduction.

- User interfaces for algorithmically driven decisions should always show the mathematical confidence or probability levels of each element. (These are often absent.)

- Show as much context as possible. All numbers must be framed so as to reduce the overly simplistic power of numerical scores. For sentencing, for instance, the interface should show other stories/cases so the current case is situated in a larger, more complex environment, rather than starkly graded against an invisible background of data.

- Use ranges rather than points.

- Add narrative wherever possible.

No, none of this makes the process anywhere near perfect or free from bias. An argument can and should be made that there are domains where AI/ML simply shouldn’t be used. But nota bene: this may simply revert those domains to more traditional forms of human bias. I find this whole topic disquieting and worthy of considerably more thought.

(See also: Leigh Dodds of the Open Data Institute has a related, interesting blog post this week: "Can the regulation of hazardous substances help us think about regulation of AI?")

This week on What's New, Joseph Reagle talks about his new book, Hacking Life: Systematized Living and Its Discontents. Joseph crystallized for me the basis for the life hacking movement, from Inbox Zero to Soylent: “Life hackers are the systematized constituency of the creative class.” When work is no longer 9-5 in a large company, but a 24/7 hustle of coding or writing or designing or anything else with little scaffolding, an obsession with productivity is a natural cultural byproduct. Tune in.

(

(