Apple's Vision + The Cost of Forever

Revisiting the original design documents for the Macintosh computer to understand why we’re in a love/hate relationship with Apple, and a comparison of how much it costs to save a book and a web page forever

by Dan Cohen

In this issue: revisiting the original design documents for the Macintosh computer to understand why we're in a love/hate relationship with Apple, and a comparison of how much it costs to save a book and a web page forever.

The recent 40th anniversary of the Macintosh gave many commentators the opportunity to laud the revolutionary computer that made Apple what it is — and also to lament what Apple has become. A short story, a fall from grace: The Macintosh as a computing experience and cultural object in 1984 felt fun and liberating, a scrappy upstart on the side of the people; now Apple is an illiberal behemoth, a tightfisted keeper of a walled garden.

If you look back another five years to 1979, however, you can see that Apple has had a remarkably consistent vision of what it wanted to make, and how it would make money from what it made. What we dislike about Apple now was there at the start, part of the company's original design principles.

In 1979, when the internal name for the Mac was still "Annie," planning conversations and documents envisioned what this new computer would be. You can read these primary sources and interviews at a Stanford University Libraries website created by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang and Wendy Marinaccio that was released shortly after the 15th anniversary of the Mac: Making the Macintosh: Technology and Culture in Silicon Valley. (I reviewed the site for an academic journal in 2002, and have written several times about the documents therein; I must admit to a bit of an obsession for reasons historical, contemporary, and personal.)

Unlike tech companies that launch products before they are fully conceived, requiring a "pivot" of those products based on perceived utility post-launch, Apple has had a strong, coherent view of its creative process and its creations. To their credit (and as some would now say, to their discredit), they have stuck to that vision for 45 years.

My favorite summary of Apple's core thesis comes from Jef Raskin, the early employee who founded the project that became the Mac. "Design Considerations for an Anthropophilic Computer" is Raskin's crisp outline not only of the Mac, but of the main themes that Apple would pursue for decades. The selection of "anthropophilic" to describe a new computer in the late 1970s might have been an unusual (and unusually erudite) word choice, but it fit the project well. As the word's Greek roots imply, this new computer would be "human-loving" or "attractive to humans" rather than complicated and techy like every other computer on the market at the time.

Everything we love about the Mac is there in the record of May 1979:

This is an outline for a computer designed for the Person In The Street (or, to abbreviate: the PITS); one that will be truly pleasant to use, that will require the user to do nothing that will threaten his or her perverse delight in being able to say: “I don’t know the first thing about computers."

With snappy words, Raskin wrote that "the computer must be in one lump," "seeing the guts is taboo," and "you get ten points if you can eliminate the power cord" and run the thing on a battery. Ideally, it would cost $500. The PITS would never have to open the machine, or better yet, could not open it, for that is unnecessarily complex. The computer would have a few small ports, or better yet, none at all. This was a striking vision for the late disco era, when wide ports spread across the surface of PCs like bell-bottoms.

Did the Mac team realize this powerful vision? Only partially — the Mac had ports and a power cord and cost way north of $500 — but this partial failure felt like a wild success to many users, including myself: a well-designed, highly usable computer that was also flexible enough to be customized and to challenge those ugly PCs at their own game. It would take Apple until much later — the arrival of the iPhone and then the iPad (both of which started at $500, ran on a battery, and could not be opened) to truly complete Apple's original vision — and thus to stoke dissatisfaction among users, software developers, and governments, because of the business model and centralized control that accompanied these rather capable lumps.

If you look carefully enough, however, everything that bothers us about Apple now existed then, in 1979. "It is expected that sales of software will be an important part of the profit strategy for the computer," Raskin highlighted in "Design Considerations." In another document, written in the fall of 1979, "The Apple Computer Network," Raskin and the Mac team realized that communications and services could make the math work for a relatively inexpensive, unexpandable device. There could be regular charges not only for software but for access to data sets and media.

In short, hardware that is a lump requires a mound of additional ongoing revenue, a process that would be overseen by Apple in its easy-to-use but closed system. There is another definition for the word "anthropophilic" in the Merriam-Webster dictionary: "attracted to humans especially as a source of food."

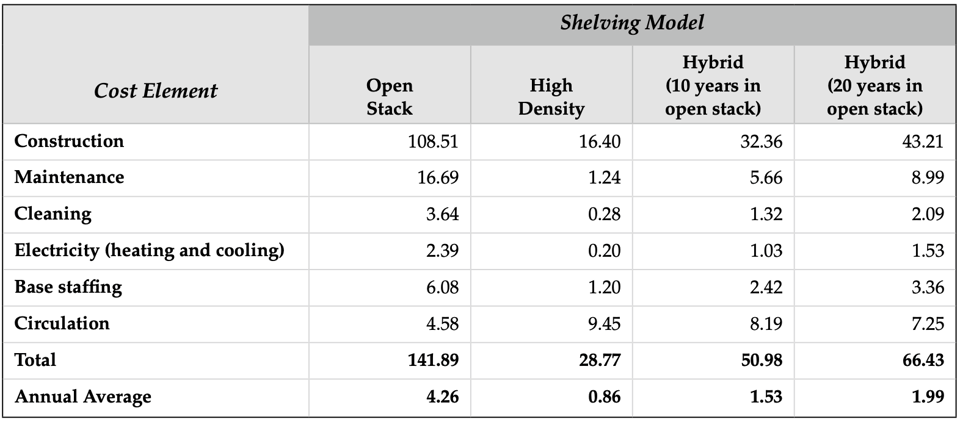

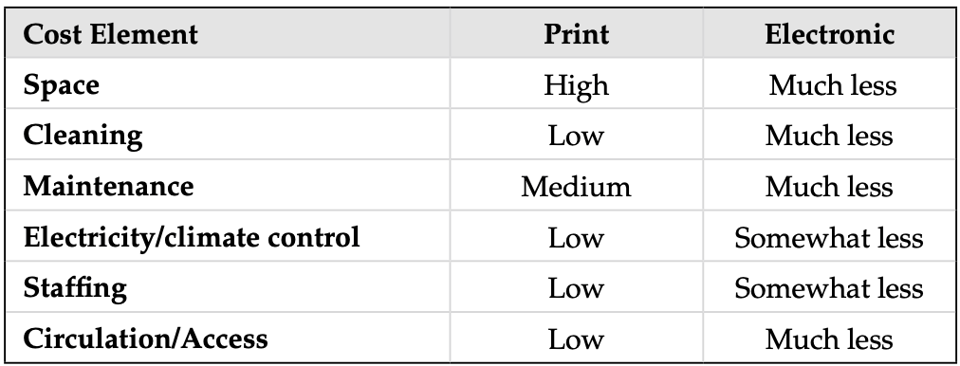

How much does it cost to save a human artifact forever? In a wonderful thought (and economic) experiment in 2009, Paul Courant and Matthew Nielsen estimated that on average it takes about $100 to preserve a book forever in a library. (A lot less if you keep that book in high-density shelving away from people; considerably more if you keep the book in accessible open stacks.) Want to save a million books in perpetuity? You better have over $100 million to store those books and cover running costs like air conditioning and staffing.

Note that this doesn't include the cost of purchasing the book to begin with, so you should probably start with a cool $200 million or more for that million-book library you're planning for your backyard. Not cheap!

Courant and Nielsen also concluded their analysis with an unsettling notion: What if it costs considerably less to keep an ebook forever?

Recently Rebecca Kilberg of the Library Innovation Lab ran this thought experiment on the digital objects stored by Perma.cc, an academic project that preserves digital links and documents forever. Perma is used by scholars and courts to ensure that sources and evidence remain accessible even if a website or server no longer works.

With our current storage cost model, over 100 years a single link costs about $0.05 to maintain, meaning 10 links cost $0.51, and 100 links cost about $5.13.

At first glance, this seems very affordable! But though this is where our calculation ends, this is not where the expenses do. To begin, we did not include the up-front cost of creating the link. Calculating up-front costs for a link would include the costs of creating the entire Perma.cc infrastructure from scratch. It would also have to account for the cost of the current Perma.cc site’s underlying capability–how we create the links themselves.

And of course there's the issue of staffing:

The most significant unaccounted cost is our labor: Perma.cc needs people to run it. Our developers add new features, fix bugs, and continually improve our code to make sure we’re serving our users. There’s also labor that goes beyond the code.

And yet more:

We also have to consider that cost can be other than monetary. When we began thinking about the costs of web archiving, one area that stood out was the ecological cost.

Computers use considerable energy, and the impact of that usage over time must be accounted for.

The preservation cost per human-created digital object is still orders of magnitude smaller than the cost of a perpetually preserved print book, but there are orders of magnitude more digital objects to be preserved. Simply put, if you have $100, you can either save one book or a thousand web pages forever. Choose wisely.