The Writing Is on the Wall for Handwriting Recognition

One of the hardest problems in digital humanities has finally been solved

by Dan Cohen

To summarize the theme of this newsletter recently: Use AI, not too much, mostly to connect with the intelligence of other human beings, not AI. Previously I’ve discussed using AI to discover books and articles in the library, and artworks in the museum; in this newsletter, how AI can help us work with the letters and manuscripts in archives and special collections.

“All goes in the usual monotonous way.” That is the depressed sigh of George Boole in a letter to his sister Maryann in 1850. It was the spark for my book Equations from God: Pure Mathematics and Victorian Faith. Boole, the English mathematician who gave us the logic at the heart of the digital device you are reading this on, was teaching in Cork, Ireland at the time. On a cold December day, he wrote to Maryann about his feelings of profound loneliness. In a city that was on edge from religious strife and famine, he played piano at home to an empty room, and took long walks by himself. At the end of the day, he retreated to his equations, which seemed to transcend the petty differences of humanity.

But before developing my thesis about the fervent emotions behind Boole’s seemingly cold mathematical logic, I first had to read his damn handwriting. Talk about monotony! There were hundreds of letters and notebooks in his drifty scrawl. In retrospect, Boole’s handwriting is actually not that bad; I’ve encountered far worse since reading his in Cork. And it helped that I had taken a brief course on paleography, the art of deciphering handwritten historical documents. But it would have saved me a lot of time getting to the interesting interpretive phase of my research if a computer could have converted his handwriting into machine-readable text, as it already could for typeset text through a process called optical character recognition (OCR).

Since I wrote that book, university and industry labs have been trying to solve the incredibly difficult problem of handwritten text recognition (HTR). OCR quickly approached 99% accuracy for digitized books, whereas even the best HTR systems struggled to reach 80% — two incorrect words out of every ten. The issue is obvious: unlike the rigorous composition of books, handwriting is highly variable by author, and words are often indeterminate and irregularly arranged on a page.

This led to a number of experimental approaches, from crowdsourcing to machine learning. At the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, we digitized the Papers of the War Department, 1784-1800, so that knowledgeable researchers and members of the public could transcribe them. Around the same time, University College London did the same with the manuscripts of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Later, the tranScriptorium Project and Transkribus used neural networks to improve accuracy, but required a significant training corpus.

Even with considerable prep work, error rates remained stubbornly high. Here’s Transkribus’s best guess at George’s letter to Maryann, above:

I am sorry to hear of Miss Davis

gent affliction. When you write

to her tele her so and also invite

her to visit you when she fal

that she can do so. I now

wish binvite you to visit me.

As mother is so much better she

may I think spare you and

the weather being colo in England

is change of air would I think

do you good Herr we have

days of the most lovely character

about twice a week At other

times it is well with intervals

of bright weather

but such day

вр/1/51<7>

Cock Dec 18 1850

My dear Sister

Your letter this morning

was a very welcome one & I wish

that I had anything interesting

to say in return But I have not

Ale gres in the usual Monotonous

way I give my lecture read

write take a long walk occasion

by & one or time a week go

out letter this is very much

the history of my life from

week to week I think I am

upon the whole I have woke

More recently, I’ve used this letter as a quick test of AI models. They have gotten incrementally better over the past three years, but I was frankly stunned when I put the letter into Gemini 3 Pro this week and asked it to have a go at the transcription:

Right Page

[Top Right Corner] Cork Dec 18 1850

[Salutation] My dear Sister

[Body] Your letter this morning was a very welcome one & I wish that I had anything interesting to say in return. But I have not All goes in the usual monotonous way. I give my lecture, read write take a long walk occasionally [try] & once or twice a week go out to tea This is very much the history of my life from week to week I think that upon the whole I have worked

Left Page

[Body] I am sorry to hear of Miss Davis’ [or Davin's] great affliction When you write to her tell her so and also invite her to visit you when she feels that she can do so. I now wish to invite you to visit me As mother is so much better she may I think spare you and the weather being cold in England a change of air would I think do you good Here we have days of the most lovely character about twice a week At other times it is wet with intervals of bright weather, but such days

Notes:

"Cork... England": The context suggests the writer is in Cork, Ireland, inviting their sister to visit from England to escape the cold.

"occasionally [try]": On the right page (line 8), the handwriting becomes very scribbled. It appears to say "take a long walk occasionally try & once or twice..." or possibly "occasionally by & once or twice...".

"Miss Davis": The name on the first line of the left page is difficult to decipher with certainty; it looks like "Davis," "Davin," or perhaps "Savin."

Gemini transcribed the letter perfectly: it figured out that the right side is the beginning of the letter, not the left (the letter actually continues on the other side of the paper, which accounts for the discontinuity between the two sides we are viewing); it left off the periods where Boole also (oddly) omitted this punctuation; and it includes a self-reflective analysis of where it might be wrong and provides alternative readings.

Even wilder, when you click on a “show thinking” tab, Gemini provides a long discourse on its approach and minute details about word choices:

Assessing Image Features

I'm now identifying key image features. The paper appears folded, with the date and salutation clearly on the right side, confirming it as the front page. The handwriting is typical 19th-century cursive, though legible. The location, Cork, and the addressee, "My dear Sister," are identified. This is helping me to prepare for accurate transcription.

Refining Text Analysis

I'm now zeroing in on a tricky word: "occasionally". I initially considered "exercise" or "every day", but the context and image suggest "occasionally," although the "y" is faint. Close inspection reveals loops indicating it's the intended word, despite the messy script. I am confident that it means "occasionally."

…

Refining Word Possibilities

I've been bouncing around many possibilities for that unclear phrase, but now I think I've cracked it. I initially tried "accompanied by," then "exercise", "excursion", and even "swimming". The letters "e" or "o" seem key to the preceding word. Focusing on the letter shapes, I am now confident the words I have are "take a long walk occasionally".

Determining Word Boundaries

I am now focusing on determining word boundaries, particularly in the phrase "take a long walk...". Initial guesses included "evening" or "exercise" for the illegible portion. But I'm now leaning towards "every" preceding the blurry term, with "evening" as the subsequent word, though "exercise" is still a contender. This leads to the phrase, "take a long walk every evening," or perhaps a variant like "exercise" or "excursion." I have reviewed the handwriting to narrow down the term that comes after "walk."

…

This thinking goes on for almost 2,000 words, and what’s remarkable is that it is essentially a verbalization of what you’re taught to do in a paleography class: assess the overall document first, determine key features, study letter shapes and strokes across the letter to refine your understanding of the particular script, consider context and word/phrase possibilities, think about the coherence of content, grammar, and usage, identify any contractions, proper names, and other oddities, etc.

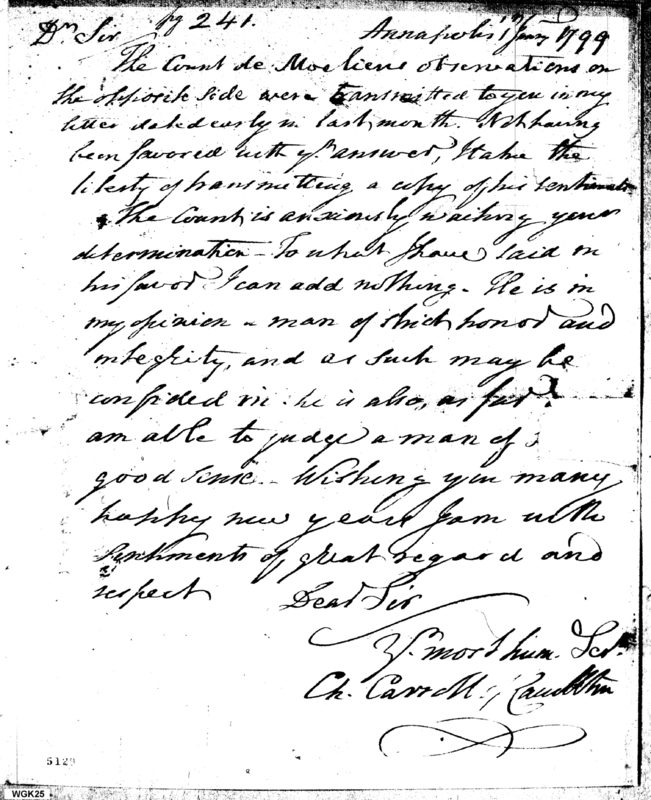

Encouraged by this AI progress, I dropped one of the letters from the War Department archive into Gemini:

And here’s Gemini 3 Pro’s transcription:

[Top Left] Dr [Dear] Sir pg 241.

[Top Right] Annapolis 1st Jan^y 1799

[Body] The Count de Moeliens observations on the opposite side were

transmittedto you in my letter dated early in last month. Not having been favored with y^r [your] answer, I take the liberty of transmitting a copy of his sentiments & The Count is anxiously waiting your determination – To what I have said in his favor I can add nothing. He is in my opinion a man of strict honor and integrity, and as such may be confided in: he is also, as far as I am able to judge a man of good sense. Wishing you many happy new years I am with sentiments of great regard and respect Dear Sir Y^r most hum. Serv^t [Your most humble Servant][Signature] Ch. Carroll of Carrollton

Notes on the text:

"transmitted": In the second line of the body, the word "transmitted" is crossed out in the original text, but the sentence is grammatically incomplete without it (or a similar verb). It is likely the author meant to replace it to avoid repetition with the word "transmitting" appearing a few lines later but forgot to insert the new word.

"y^r": This is a common 18th-century abbreviation for "your."

The Signature: Charles Carroll was the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence and was known for signing his name as "Charles Carroll of Carrollton" to distinguish himself from his father and other relatives with the same name.

Another perfect job. Maybe too easy?

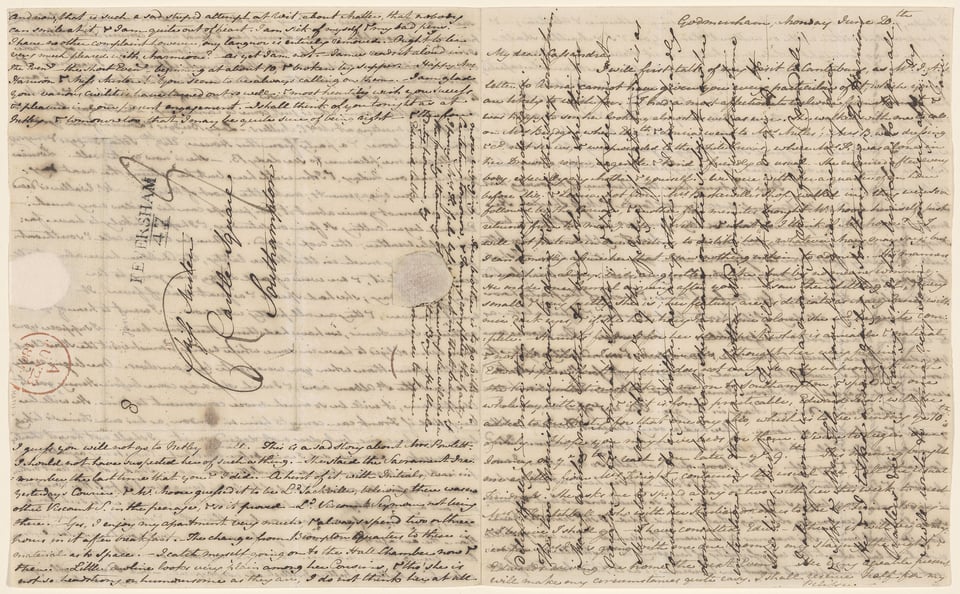

Time to bring out the final boss: Jane Austen. A letter to her sister Cassandra held in the Morgan Library:

May your courage always rise, Gemini.

Right Page (The beginning of the letter)

[Header] Godmersham, Monday June 20^th

[Salutation] My dear Cassandra

[Body] I will first talk of my visit to Canterbury, as Mrs. J. A.'s [Jane Austen's sister-in-law] letter to Anna cannot have given you every particular of it which you are likely to wish for. I had a most affectionate welcome from Harriot & was happy to see her looking almost as well as ever. She walked with me to call on Miss Bridges, when Mr. K. Valpy [?]...(The text continues but becomes heavily obscured by the vertical cross-writing)

Ok, this one’s hard for even a seasoned Austen scholar, with bleeding from the other side of the letter and extensive cross-writing. (Austen turned the page and continued writing at 90º to the first part of the letter to get more onto a single sheet; this was not uncommon in the nineteenth century, and rather annoying.) Gemini does the right thing here: rather than venture a guess like a sycophantic chatbot, it is candid when it can’t interpret a section of the letter. Nevertheless, it went on to get most of the horizontal text correct and some key phrases from the cross-writing too.

At this point, AI tools like Gemini should be able to make most digitized handwritten documents searchable and readable in transcription. This is, simply put, a major advance that we’ve been trying to achieve for a very long time, and a great aid to scholarship. It allows human beings to focus their time on the important, profound work of understanding another human being, rather than staring at a curlicue to grasp if it’s an L or an I. Could we also ask Gemini to formulate this broader understanding? Sure we could, but that’s the line that we, and our students, should resist crossing. The richness of life lies in the communion with other humans through speech, the written word, sounds, and images.

If we want to use AI more extensively in the classroom, we can actually take it in the opposite direction, folding its HTR insights back into human comprehension. Take Gemini’s 2,000-word thinking analysis of Boole’s script. I could imagine using that with students in a paleography class to help them understand the steps in the process of deciphering a letter or manuscript. After a few examples, guided by this clever narrative feature of AI, students could become independently able to read these texts.

Was it nice to spend a month in Cork trying to do this deciphering on my own, without AI assistance? It was! Cork’s a wonderful city. Did the long time it took to read each letter provide some mental space for initial thoughts for the book? Maybe! But if you talk to historians now, they will admit that they can’t spare the expense and time of leafing through letters over a month in a foreign city. Most simply take photos of documents in quick trips to the archives and review them later, at home. This makes tools that help one gather and organize archival documents, like Tropy and Sourcery, even more valuable — especially with AI now able to make these digitized copies searchable and readable.

If AI can diminish some of the monotony of research, perhaps we can spend more time thinking, writing, playing piano, and taking walks — with other people.