The Stones of Newton

The history of a famous bell tower that is in danger of falling

by Dan Cohen

No one is quite sure when it happened, but a stone fell off the face of a nearby church bell tower a few years ago. Over the subsequent months, three dozen more followed the first stone to the ground, and the tower was clearly in danger of collapsing into the church or onto our town’s main street.

The name of this crumbling tower? America. Literally. The church was, for a time, the pulpit of Reverend Samuel Francis Smith (1808-1895), who authored the patriotic song “America,” better known as "My Country, 'Tis of Thee.” A century after Smith penned this unofficial national anthem, they named the bell tower after it. The tower and the church, The First Baptist Church of Newton Centre, Massachusetts, are on the United States National Register of Historic Places.

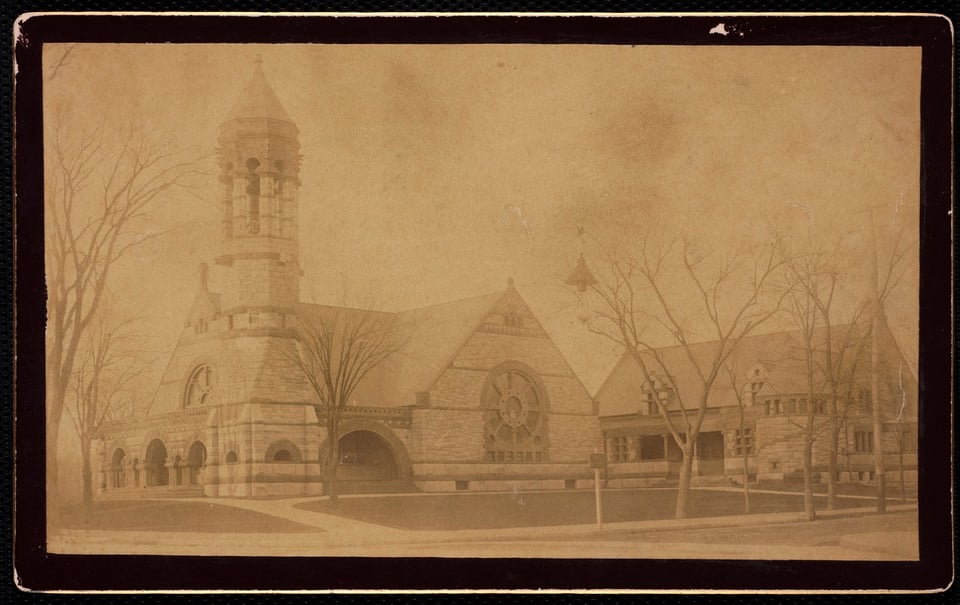

And richly representative of America they are. The church was built and rebuilt several times, and the celebrated version we now have is by the architect John Lyman Faxon (1851-1918), who adopted the Romanesque Revival style of H. H. Richardson, America’s architectural genius of the nineteenth century. Like so much of emerging American art and culture, Romanesque was a spirited fusion of historical and global influences that shouldn’t have worked (and sometimes didn’t), married to the American proclivity for instant gravitas through sheer mass. Just look at this beautiful pile: The stone facade, archways, and tower common in medieval European churches, along with Syrian and Byzantine influences like polychromatic stonework and ornamentation; also, its horizontal stretch to fill the lot like a McMansion, and its echoes of secular buildings in the area, like Newton’s train stations. Faxon was deeply influenced by John Ruskin, especially his art and architectural history The Stones of Venice; First Baptist shows the appreciation for the meaningful labor, long-lasting religious art, and civilizational uplift that are embedded in the rough-hewn stones of the old-world mason.

If you step inside the church, which has grand wood ribs arching over an ovoid interior, you would not be wrong to feel as if you were inside a whale. This, too, seems appropriate given that Reverend Smith wrote “America” at roughly the same time that Melville wrote Moby-Dick. The stones used on the exterior even come from Gloucester, a former whaling town on Cape Ann in Massachusetts. A whale of a building, beached inland. There are sometimes epic readings of Moby-Dick in Gloucester; I have long thought that they should stage a reading of the famous, incendiary sermon about Jonah by Father Mapple, a former whaler himself, inside First Baptist. It just fits.

Now there’s a fence around America, and an increasingly elaborate structure holding it up—first made of wood, then steel pipe scaffolding, and most recently gigantic iron I-beams. The tower is being repaired with funds from both the church and the city, as well as other public and private donors. Everyone in town still looks at the tower as they walk by and worries about it falling down before it can be fixed. They are working on it. It’s the slow, deliberate work of traditional stonemasons.