The Library’s New Entryway

An interface that combines the advantages of the traditional index with the power of LLMs is the path forward

by Dan Cohen

Until last month, these were the ways I had found articles and books in a library: the card catalog (classic); the card catalog on microfiche (steampunk); the online public access catalog (OPAC) at a fixed terminal (bland); Z39.50 at the command line (cyberpunk); the CD-ROM (fleeting); and the library website (the new classic).

Despite this great variety, underneath all of these tools was a common technology: the index. Those articles and books I sought had been encapsulated in set of words — descriptive metadata — that were arranged in a structure that made the entire collection searchable, words seeking their twins. The way we have scanned that index for relevant items may have changed from physical to digital, and gotten speedier and more complex (through add-ons like Boolean operators and faceted browsing), but throughout, the index has been the entryway into the vast riches of the library — and most other large collections.

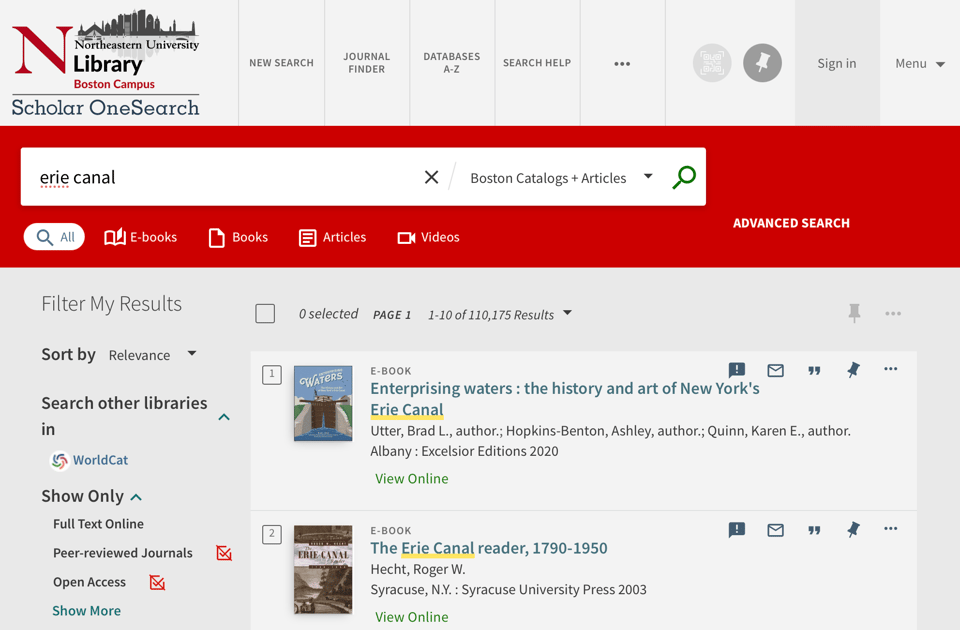

That is about to change. Suppose you’re a first-year college student researching the history of the Erie Canal. (It opened 200 years ago this month!) Typing “Erie Canal” into the library website search box — that is, asking it to match your terms with the library’s index — gives you a startlingly high number of texts to consult:

The Northeastern University Library has over 110,000 items related to the Erie Canal, including over 20,000 articles. Many students understandably find this scale intimidating, akin to a Google search that returns thousands of web pages. Because it’s 2025, they increasingly turn to an LLM, like ChatGPT, to start their research, rather than Google or the library website. Here’s what that looks like for an Erie Canal request:

Whatever you think about AI chatbots, you should recognize some significant improvements here: The student can inform the LLM more specifically about what they want, in natural language, and the chatbot’s response can reduce the clutter of a broad search during a helpful secondary process of analyzing and selecting appropriate items. On the down side, and largely invisible to that first-year college student, it mostly returns popular articles and images it has found on the web rather than in-depth scholarly work or special collections, and this is true even if pressed into a higher-level research mode. (ChatGPT extensively uses retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) for such queries, where it does its own web search and uses those web pages to supplement the innate knowledge of the LLM.) Also, although less frequently now, it can hallucinate citations and especially quotations from articles and books if pushed for more information. (OpenAI recently released research noting that it was impossible for LLMs not to do this at least some of the time.)

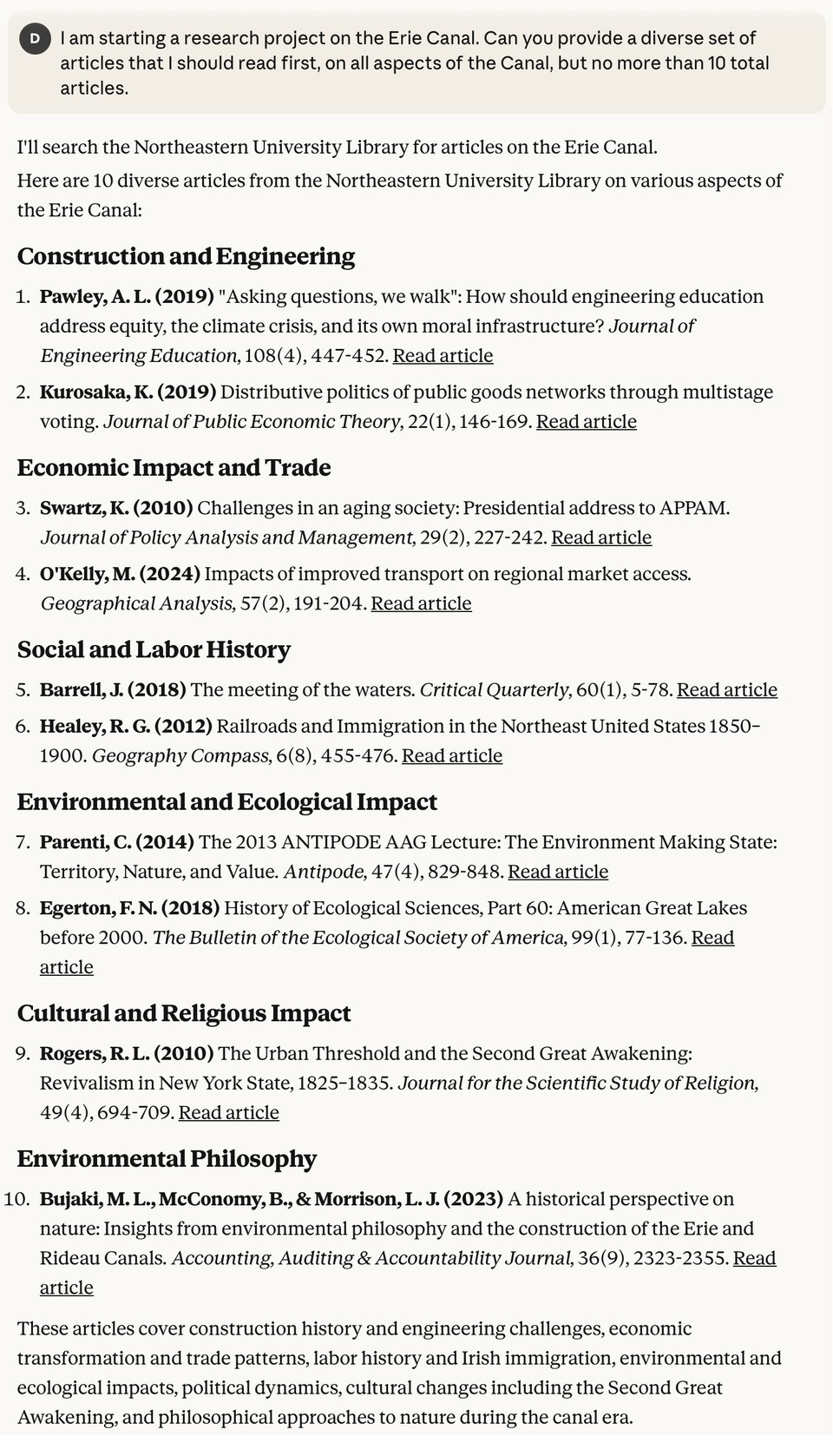

What if we could combine the LLM’s better understanding of a student’s aims with the rigorous index and robust collection of a research library? That’s what our new Northeastern University Library Model Context Protocol (MCP) server and plugin for Claude does. Here’s the same student, using NUL + Claude:

This is, in my mind, the best of both worlds: Claude, as a sophisticated large language model, is tasked with what it does well, discerning scope, content, and related information. The plugin is only triggered when the researcher seems to be doing academic work; it then connects to the library server for what I’m going to call LAG, or library-augmented generation. Because it relies on vectors rather than indices, Claude is also less rigid than the library search box, enabling it to formulate flexible library requests — words seeking not only their twins, but also their cousins. (More on this difference between vectors and indices in a forthcoming newsletter.)

Claude then passes off its savvy digestion of the student’s query to our library’s MCP server to locate 100% non-hallucinated resources that can help the student. A secondary server creates direct links right to the articles held by the library, including both open access and gated papers. This output encourages the student — or the faculty member or the general public — to consult the texts themselves, which popular chatbots eschew during spasms of summarization. Instead, through our software we want to foreground the expressive works of human beings — the articles, books, documents, and works of art, rather than the AI’s digests of these objects.

Our methods here only loosely couple the library and the AI, as I detailed in a prior newsletter. With our MCP server, we can easily use any LLM or chatbot, including open source ones, as the interface for our library, and none of the library materials in this system can subsequently be used by the AI for training. This offers some navigation around criticisms about AI being culturally extractive and environmentally problematic (instead of Claude, we could switch to small language model running locally). For fellow faculty members I have shown this to, it also represents something of a relief, as a way to incorporate the use of AI into their teaching and research without feeling that that technology is necessarily a replacement for scholarly research and writing.

I will have much more to say about all of this in future newsletters. Given how compelling the fusion of LLM front-ends with library back-ends is, we are unsurprisingly not the only ones working on it, and I want to highlight some other work being done, the significance of the overall concept, and some use cases for teaching, learning, and research. However, I do want to highlight what is implicit in our work on the NUL MCP server and Claude plugin: that this technology should be library-driven and -controlled, and that ideally it should work seamlessly across the entire surface area of a library’s collections, in the way that students and researchers will expect.

For now, a big thanks to Ernesto Valencia and Greg McClellan of the Northeastern University Library tech team for developing both our MCP server and the Claude plugin.