A Hero's Iconography

A shocking photograph featured a brave man — and visual echoes of the art he loved

by Dan Cohen

On this Martin Luther King Jr. Day, it is helpful to remember that heroes still walk among us. One of them is Ted Landsmark.

Dr. Theodore C. Landsmark’s wide-ranging biography and profound impact are impossible to contain in this small space. He has been a powerful civil rights leader, thoughtful urban planner, and scholar and administrator in the realms of public policy, culture, and community work. At Northeastern University, where we are colleagues, it was wonderful to see him celebrated last week for the incredible influence and change he has brought to Boston.

Although he has had such a great impact in so many ways, Landsmark will probably be known decades and even centuries from now for being at the center of one of the most infamous photographs in twentieth-century American history:

That’s Landsmark in the suit on the right, being attacked by a teenager brandishing the American flag. I interviewed Landsmark on our library’s podcast soon after I arrived at Northeastern, mostly to discuss his work on the design of cities. But since I grew up in Boston and lived through the tense years of desegregation and the busing of students outside their neighborhoods to integrate schools, I did want to ask him about what happened on April 5, 1976, and his perspective these many years later. Here’s the story behind the photograph, as narrated by Ted on the podcast:

I was on my way to a meeting in Boston City Hall, where ironically, we were going to discuss ways of increasing minority participation in construction projects going on in neighborhoods of color in Boston. I was running a little late, and I wasn't really paying a lot of attention. I came to a corner adjacent to City Hall without realizing that a crowd of high school students primarily were turning the corner in the opposite direction. We started to pass each other when the leader of the group, who was carrying an American flag, reversed his direction along with a couple of other kids, and they came back to attack me. They had been at a meeting with Louise Day Hicks, who was an anti-busing leader, who was on the Boston City Council at that time.

She had gotten them really excited and riled up around the racial issues in Boston. I was, I think, the first African-American that they encountered coming out of City Hall. They were angry, and upset, so that small group attacked me and then ran off with the rest of the crowd of more than 100 kids to demonstrate outside of the court house of the federal judge who had ordered busing in the first place. I was very quickly approached by a reporter, who was covering the event, and he took my name, and asked where I was going. Then, he ran off to follow the crowd. At that point, a police officer got to me, and said to me "Gee, you okay here? We saw what happened, and we've called an ambulance. Let me escort you to where the ambulance is."

Landsmark’s nose was broken, but his spirit was not. He had marched on Selma and Washington with Dr. King, and wanted to turn his injury into a lesson about the sources of ongoing racism. Critical to this reframing was Landsmark’s deep understanding of the power of images, influenced not just by his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, but by his appreciation and knowledge of art.

First, he ensured that the photographic record would not be clouded by images that could be interpreted in other ways:

[The policeman] took my arm help me across City Hall Plaza, and I immediately asked him not to hold my arm, because I'd been involved for a number of years in civil rights activities, and I was aware that if there would be a photographer available taking a picture of the events, that that photographer would get a photograph where people would think that I was being arrested. I asked the police officer to please let go of my arm.

Then, when he was in the police station, the officers who were trying to identify the perpetrators brought Landsmark the photos of Stanley Forman, a photographer for the Boston Herald American who had just won the Pulitzer Prize the year before, and happened to be at City Hall Plaza when Landsmark was attacked. (Ted, at our celebration last week, with a sly smile: “It was helpful to have a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer nearby.” Forman would soon win another Pulitzer.) As Landsmark scanned Forman’s photos, he immediately knew that one of them, with a menacing teenager swinging the American flag at him, would be on the front page of newspapers not just in Boston, but around the world, the next day. He called his mother and said just that.

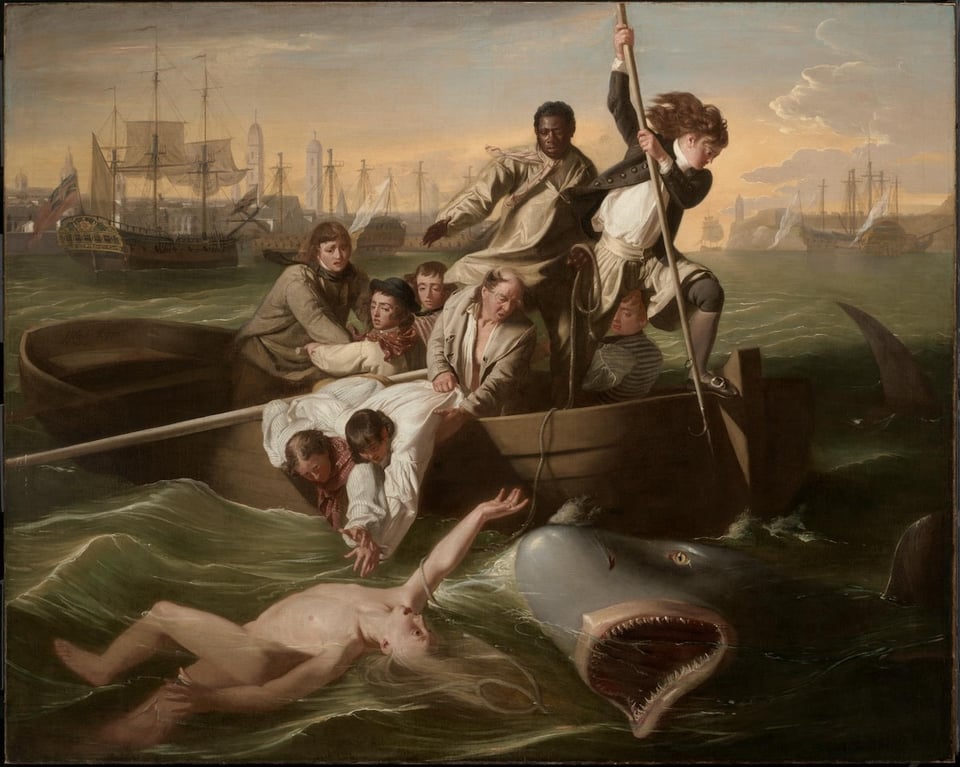

The reason for this confidence came from decades going to art museums, often with his mother. Landsmark knew how the composition of a scene could create tension and invoke feelings of heroism and disgust. In his mind’s eye, looking at the key photograph at the police station, he recognized visual motifs from John Singleton Copley’s painting “Watson and the Shark,” another image in which a spear divides the canvas in a moment of shock and action (and also, as Ted recalled in a short film shown at the celebration, with a Black man at the center), as well as Paul Revere’s “The Bloody Massacre,” a rendering of another traumatic event in Boston and American history. Landsmark was intimately familiar with both of these potent images from his frequent visits to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

The best art, Landsmark also knew, moves the viewer from the specific to the general, from a historical rendering to larger, enduring themes about our humanity. In the hours and days after April 5, 1976, he didn’t want the assault to be about him, or about the teenagers who attacked him. Indeed, to this day Landsmark points instead to the adults who riled the teenagers up, and the social context they were embedded in. He hoped that Forman’s photograph would help many others reach this same, broader conclusion. The public’s attention would, through the force of visual art, move to the deeper issues the image summoned.

In his book on Landsmark, Forman, and 1970s Boston, The Soiling of Old Glory: The Story of a Photograph That Shocked America, Louis Masur underlines the importance of art history to the enduring power of this photo:

We carry historical and visual memories and associations to every image that we see. Sometimes we are conscious of those associations, as might be the photographer who plays off of them. For example, when Gordon Parks posed Ella Watson in front of an American flag, he relied on viewers’ knowing Grant Wood’s American Gothic, which had already become a visual icon in American culture. More frequently, it is not that we are conscious of a specific connection but that the composition of any one image suggests the forms, positions, and expressions of others, and those associations deepen the reading of any single picture.

Landsmark’s comprehensive knowledge of art allowed him to instantly identify what would connect with the millions of viewers of Forman’s photograph, and stir them not only to sympathize for one human being, but to see the racism that was still pervasive a decade after the assassination of Dr. King, and which needed to be fully addressed for the flag to represent all Americans, and be proudly raised again, unsoiled.